The shape of things to come

A brighter future for people and planet

Dissonance and Discomfort

Posted on January 26, 2026 By shapeofthingstoni in Ethics + Institutions & infrastructure + Politics & society + Volunteering & activism

January 26.

Yesterday I awoke to the city blanketed in smoke. Not the familiar eucalypt sting of open forest, but the ashy smell of ferns and moss. The Otways fire had broken containment.

Fire season runs from November to March, more or less, though it’s getting longer each year now. 20 days ago, when the last heat wave barrelled through, catastrophic fires flared across the state, five of which – including the Otways – continue to burn.

Rainforest is on fire, the high country is on fire, and tomorrow will be 45oC here in the city, and so much worse north of the ranges. Places I love, that nourish my soul and bring me joy, are being destroyed. Irrevocable changes to ecosystems that never evolved with fire.

I am so sad.

…

January 26.

I also awoke to news of another ICE murder in Minnesota. I read the stories, horror compounding on the kidnappings, beatings and murders that came before; countered by admiration for the people refusing to comply, calling fascism what it is, and taking power back from the MAGA goons.

I wondered why it took a white man’s death for voices with actual power to speak up: Obama, Clinton, the few non-complicit media org. Why aren’t black bodies, latino bodies, women’s bodies, ever enough? And yet I’m relieved that – finally – Americans are waking from the reassuring delusion that this is just something to be withstood until more elections roll around.

The discomforting truth is that US institutions have fallen and the world has irrevocably changed. The old equilibrium is destroyed and a new stable point will need to be fought for, not just by Americans, but by all of us.

I am so anxious.

…

January 26.

The date a fleet of ships bearing the flotsam of England in crisis, landed to establish a prison colony on Gadigal lands, in the place now called Sydney. The imposition of colonialism and the commencement of genocide, ecocide and brutality that continues today; our national holiday – “Australia Day”.

Today, Nazis marched through the city known as Melbourne and naarm, land of the Kulin Nations. White supremacist scum repeating the tactics of Trump and his team swell their ranks here, selling simplistic solutions to complex problems to the angry and ignorant. Lies that justify their feelings and fan hate toward everyone outside of their tribe. First Nations people, non-white people, intellectuals and activists: targets to blame and distract attention from those growing rich off discontent and discord.

Five days ago our Parliament passed poorly-drafted new “hate laws” that allow the criminalising of dissenting opinion and suppress valid criticism of the genocidal Israeli occupation of Gaza, equating political critique with antisemitism, yet do nothing to address this white nationalist trash in our streets with their “March for Australia”.

I am so angry.

…

January 26.

Tomorrow is my birthday. I don’t feel like celebrating. Instead, I’m reflecting. What am I doing about the climate crisis? What am I doing about rising white nationalism? What am I doing as authoritarianism creeps into Australian politics? Where do I stand as techno-fascism ravages resources and reshapes minds into mush incapable of sitting with discomfort?

I didn’t go to the Invasion Day marches today. I tell myself I’ll write to my MPs, yet I haven’t. I’m not a member of Extinction Rebellion or Just Stop Oil, despite understanding just how much is at stake. I tell myself I’ve dedicated my entire career to fighting for things to be better, yet I understand how much of that is a privilege: that I’ve been able to choose work that aligns with my values, and to make a middle-class living off the public good.

Dissonance.

While raging on social media to an audience of my peers won’t change anything, neither will numbing out my feelings, nor feeling powerless and dejected. If I’m not choosing the frontline, I risk being sidelined, ineffectual and cotton-wool wadded against these hard truths and an unravelling world.

Chaos seeds opportunities for once-unimaginable change, and the direction that change takes depends on who is fighting for it. The times call us to stand for what we believe in. So how do I fight? What privileges and protections am I prepared to shed? At minimum, I must be aware of my choices and self-justifications.

I am anxious, frightened, heart-broken, horrified, furious and exhausted. I am NOT powerless; it is NOT hopeless.

So then, choose something different.

Share the conversation:

Holding place

Posted on April 21, 2024 By shapeofthingstoni in Uncategorized

I’ve been quiet here for a very long time.

What has there been to say? I’ve no words of hope or inspiration. No candle to hold against the dark.

As the years accrue, so too do the problems. We’re living through polycrises: great tectonic shifts in the way our planet functions, the implications of which we still don’t really understand. Climate change is beginning to bite, with record-smashing droughts, floods and fires, the beginnings of mass displacement and famines. Biodiversity is in freefall, fertile soils are disappearing, we’re still living through the covid pandemic and new data on pollutants shows that every place and each one of us is contaminated with microplastics, PFAS and other ingenious human inventions. Inequality is on the increase, globally, alongside a turn to authoritarianism, right wing populism and intolerance. We’ve atrocities in Ukraine and Gaza. Afghanistan, Sudan, Myanmar, Yemen and Syria still smoulder. Trumpian politics threatens the United States once more.

Peaceful co-existence and multi-cultural harmony are artefacts of stable, largely equal societies where citizens feel enough of an abundance to welcome and share. Complex problems require multifaceted solutions and difficult compromises, backed by a willingness to change. Political populism and partisanship, unpinned from fact in our post-truth era and backed by vested interests, undermine our capacity to address the critical needs of our societies and face this difficult future. In the face of so much risk, the richest see only the opportunity to profit, believing sheer wealth and climate bolt-holes will mean they and theirs will survive the turmoil to come, but money won’t buy a functional biosphere, or the social constructs, systems and institutions needed to provide world class medical care and research.

What is there to say in the face of obvious madness?

I’m 45 now. I’ve spent half my life trying to make things better in a world that’s getting worse. I’m questioning if anything has been worth it, feeling like I’ve sacrificed too much for too little and finding it hard to belong much of anywhere after living so much in the spaces people prefer to ignore and avoid. It’s human nature to avoid pain and discomfort, and when you can’t change the system there’s a perverse sense in numbing yourself within it. Surrender to the algorithms, to the continual marketing and dopamine-system hijacking. Elevate the economy to God-King and sacrifice our life systems to it in the hope that poverty will stay someone else’s problem and we can keep the comforts the system buys our loyalty with.

See, this is why I don’t write any more. When there’s no light to shine, what help am I to anyone?

Our problems are structural, yet we’re still sold the lie that the solutions lie in individual choices. No amount you and I reduce, reuse, recycle will fix this mess. No feel-good protest will free us. It’s hard graft to wrest back some political power, to learn to work collectively and make shifts at meaningful scales, and we’re undermined all the way by the systems and structures we’ve built our societies from. How do you convince people to tear down what they depend on? How do you convince people they need to lose – assets, material comfort, perceived security – in order to win? I struggle to even convince myself, let alone find the charisma and strength needed to bring others with me. I’ve utterly failed at finding my tribe and working collectively.

I can’t call on you to sacrifice the things I’m not willing to surrender myself. I too want a safe home, a warm bed, a full belly, the protection of the law and other services of the state. And I’m so very tired. I need to rest.

What is there to say?

Rest. Love. Play. Sing. Talk. Connect. Don’t take for granted what we have while it’s still here. Live.

Photos: Lake Mungo National Park, south-western NSW, Australia

Share the conversation:

On networks, platforms and connection

Posted on April 17, 2024 By shapeofthingstoni in Uncategorized

I quit Twitter last year: reached a tipping point one day and hit delete. While I don’t miss what the platform had become, I do miss what it used to be, for me.

Over many years, Twitter was where and how I grew both my professional and personal community. It allowed me to reach, connect and converse with a diverse range of experts and people with rich life experiences. It broke down disciplinary silos and nurtured knowledge sharing. I could learn from and share ideas with scientists, farmers, development professionals, urban planners, lawyers, researchers, policy-makers and local heroes dedicated improving their lands and communities. I met so many people who were generous with their time and knowledge, and connected over shared values of environmental care and social justice.

It was a remarkable time to be online and I remain deeply grateful for the experience. Joy sparks each time I catch one of my Twitter clan on a podcast or panel, when I see a new book with their name on it, or their work makes the news. There’s melancholy too: for the kind souls I met who’ve passed, and the virtual friendships left behind.

It all makes me wonder: how do we best nurture and protect community spaces in the techno-feudal age? The internet is now narrowed and corporatised; “content” farmed for profit replacing the creative wilds of human expression, meaning-making and interconnection. We build ourselves collective spaces only for them to fragment again as the platforms change. Algorithms direct us into passive click-consumption or outrage-driven shallow “engagement”, dissuading deep, nuanced conversation. Yet connection is intrinsic to humanity: we need each other.

Places we can share, learn and grow together are essential, and increasingly rare both on- and off-line. How do we hold space for ourselves as collectives from here?

Share the conversation:

A Just/Joost Solution

Posted on November 6, 2022 By shapeofthingstoni in Uncategorized

We can build sustainability into the way we already do things, or we can push for systemic change. Each approach has it’s strengths and weaknesses, which are important to think through and discuss to work out what kind of future we want to develop.

I’ve made my own attempts at transportable food gardens in rental housing, though nothing close to a closed loop system.

It’s urban agriculture month, marked by the very welcome and much delayed return of warmer, sunnier weather, and a flurry of talks, events and open gardens here in Naarm (Melbourne). Last night I went along to a screening of Greenhouse by Joost, which tells the story of the closed loop exhibition house developed by Joost Bakker from idea to conclusion.

The flagship of Joost’s Future Food System initiative, the greenhouse operates entirely from the food and energy it generates, and is built from fully recyclable or compostable materials designed to suit modern urban spaces and aesthetics. All nutrients and continuously cycled through system elements including aquaculture, composting, biodigestion and worm farming. The surplus worms feed the fish, the fish waste fertilises plants, the fish and plants feed the humans, the human and organic waste provide natural gas for cooking and hot water, and more nutrients for the plants. It’s an ingenious system designed to make us rethink housing design, materials, land use and other big challenges facing large cities.

Watching it though, a little niggle lodged in my brain. Joost’s solutions and innovations – as valuable as they are – remain tied into the culture of the individual. Running a house like the greenhouse means you need , you need:

- To own property, allowing you to design in core elements like solar and battery power, rainwater harvesting, and biodigestion.

- A site with the right conditions (light, orientation, wind protection, climate, etc.) to produce enough food for the inhabitants.

- To have the resources to cover the high upfront costs (offset long-term, but still requiring that initial injection of capital).

- The time to set up and then maintain the system (Joost reckons half an hour a day to maintain it, though you can’t leave it for more than a couple of days and any maintenance skipped needs to be caught up later).

- The skills and time to cook from first principles and feed your household from what you grow, including unfamiliar and high-labour foods.

My local community garden is a wonderland of shared land, skills, tools, time and abilities, with a mix of individual plots and shared plantings, including composting. We’re interconnected among ourselves and keen to expand connection to the neighbourhood around us, recognising that we represent the more privileged and whiter residents.

So how do we take the significant positives of the greenhouse and apply them to urban and suburban neighbourhoods at the scales we need to meet the project’s lofty goals of reducing waste, improving food security, reducing carbon emissions and cooling our cities? Joost himself believes that there are enough people who love gardening who would be willing to grow surplus for others. That may be true, though we lack systems for effective cooperation and redistribution of surplus home produce. That’s a firm goal to work toward.

Trickier yet critical, I think, is developing shared, collaborative systems that push back against this assumption of individual ownership, accountability and action. Solutions for suburbs with socio-economic stress, high rental rates, little private space. Options for those poor in the time, skills, mobility and social networks required for the Joost model to work. Ways of delivering those sweet benefits to the communities with less, by working at the systems scale.

I’m excited to explore approaches that are intersectional and inclusive, that can work for renters and refugees, the time and money poor, the unskilled and excluded, the disabled and the disconnected.

I’m hungry for ideas on more sustainable food systems that incorporate social justice.

What can we take from community gardens and co-ops and expand? Where do we need to be challenging the regulations, structures and funding models that govern property rights and shared urban spaces? What great ideas have you dreamt up or seen in action? What other domains and initiatives can we learn from to challenge the cultural fantasy that everyone can be a stand-alone home owner?

Let’s talk!

Share the conversation:

Running laps

Posted on December 31, 2021 By shapeofthingstoni in Uncategorized

New year’s eve, 2021

Another loop around the sun completed, and like the vast majority of the world, I am exhausted. Living through the combination of grinding pandemic, climate breakdown and political dysfunction really does take it out of you, and the outlook ahead is for ever more of the worsening same.

It’s up to us. Our ability to guard our energies and influences. Our capacity to prioritise action and connection over depression and isolation. Our skills in working individually and collectively to challenge and change the systems and structures around us.

It’s beyond time we moved beyond protest and directed our anger and fear into meaningful, organised action. And its oh so hard to do so when you’re already exhausted.

We need to nurture ourselves. To step back from the relentless news cycles and social media screaming. To connect with those who inspire and motivate us. To develop rewarding and constructive ways of working together, exploring this evolving pandemic space and the possibilities and opportunities that come with rapid change.

We can tap into the power of our communities. From school committees to local councils, from sports clubs to libraries, we can grow individual action into something stronger. We can share our skills and build resilience through this time of crisis. We can move beyond the environment movement, stretch ourselves into intersectional collectives that imagine and implement local solutions to shared challenges. We can network and collaborate to reach the scales we need, leading change from the bottom up where we can’t shift the power centres at the top.

We can organise and attend working bees; growing trees, building gardens, cleaning pollution, sharing food, fixing bikes, helping our neighbours and our communities’ most vulnerable.

We can accrue our own power and influence; nominating for Boards, organising for Independent political candidates who share our values, standing for office ourselves. We can move our banking and investments out of fossil fuels and armaments. We can attend shareholder meetings, council meetings, community consultations.

This pep talk is for me. I, who have lapsed into social-media despair and exhausted inaction. Me, who is frustrated by the pointlessness of protest that is ignored by established power. This pep talk is for all of us, who find themselves a little adrift after the stormy seas of the last two years and can see the red sky morning.

In 2022, I am:

- Signing up for my local community garden

- Growing and planting native plants for the Tree Project

- Visiting the community centre and library, to see what groups exist that share some of my values, and/or creating one

- Participating further in Regen Melbourne, making connections and collaborating to support shared aims and learning to make change happen

- Curating my social media feeds and reducing my online exposure to emphasise possibilities, opportunities and supportive networks

- Using my networks, skills and knowledge to connect others and contribute to actions that are bigger than myself and my personal sphere of influence.

Inspire, support, soothe and assist each other. It’s up to us, together.

Share the conversation:

I see you

Posted on January 1, 2019 By shapeofthingstoni in nature photography + Photography

Well hello there 2019. Didn’t you turn up rather suddenly!

It’s been a while. What have you been up to? Tell me what feed your hope these days.

Share the conversation:

Property of privilege

Posted on May 24, 2017 By shapeofthingstoni in House & home + Politics & society

In the crooked old house in Kensington the morning sun sluices across the long-neglected garden to spread across the worn timber floor. Out the back there’s a compost heap seeping life back into sleeping soils in preparation for Spring. In the evenings my newly-hung curtains hold the warmth in and the house cracks its bones. It’s all starting to come together, but now I’m leaving…

I rent, and in the mess that is the Melbourne housing market my rights are few and my money limited. Situations change and I must move out and on. A new space to try to make home, finding harmony with strangers and making peace with the required compromises. No food scraps returning to soil, no renewable energy contracts, no walkable neighbourhood tucked into a corner of the inner city.

It’s a disappointing reminder that for so many of us, sustainable living is an out-of-reach privilege. We’re priced out of the suburbs with great public transport and farmer’s markets. We’re forced to move at the whim of a landlord or a rise in budget-stretching rents. We live where the work is and move when that changes, leaving behind friends and community; the imprints of our lives. It’s a modern malaise with high costs for our personal wellbeing, the community and our environment, all compounded by a system that was never designed for these sorts of stressors.

Hobart’s small-city magic means capital city facilities in a smaller community

Packing my life up yet again provides a poignant reminder of my own past privilege: an inner-city cottage within walking distance to work in an urban miracle called Hobart, Tasmania. How lucky I was to have that, and how lucky are those who still do, so long as luck and privilege are the keys to sustainable housing dreams.

What if it were different? What if we designed our cities, our economies and our communities in different ways? There’s wealth of ideas out there on more human systems and structures that value more than maximum profits and deification of economic growth. There are ways to plan cities that build in social and environmental justice (fair access to services and shared impacts of pollution and development); ways to build housing that fosters community and reduces environmental impacts; ways to structure work that balance security with flexibility. There are ways, too, of addressing the rising inequality that concentrates wealth and power in the hands of the few, though none of them easy.

I’d like to explore them. To look at ways to take sustainability from a nice thing to do if you can afford it, into being the way things are, an integral part of our systems.

For now, I’m saying farewell to the community gardens and cute cottages of Kensington and heading out into a housing estate in the ‘burbs, accepting my circumstances and making do as best I can. At least I’m pretty good at packing these days.

My street no longer, one Melbourne morning

Share the conversation:

Sketching out the shape of things to come

Posted on May 7, 2017 By shapeofthingstoni in Meta

My name is Toni.

I live in a creaky old house in inner-city Melbourne with a serious lack of right-angles and a garden I don’t get enough time for. I work in the intersection of water and agriculture, aiming to support food production that will keep regional towns going in balance with protecting the environment. My job is to balance environmental, social, economic and cultural needs and values in the frameworks used to manage irrigated agriculture across Victoria. It’s my kind of gig.

Work is what keeps me tied to the big city, a place that never quite feels like home. As much as I can, I get out of the city to go adventuring in the mountains, forests, coasts and cliffs that nourish my spirit and feed a deep connection with nature and our human place in it.

I worry for the future: climate change distresses me and the failures of our current socio-economic systems are self-evident yet those with power aim to keep us on this self-destructive path. The current politics of late-stage neoliberal capitalism makes it harder than ever to find meaningful ways to make a difference. That doesn’t stop me trying.

Over the last 5 years or so I’ve been exploring ways to try to leave this incredible planet in a better state than when I arrived on it. From personal changes through to political action I’m learning about what the issues are and where the power lies to effect change. I also try to balance this with living a full life and accepting that I too am part of the system that is overtaxing Earth’s ecosystems.

I want to help create new ways of being; a culture, and economy and a society that is more communal, more joyful and ultimately sustainable. I’d love for you to join me.

Share the conversation:

Grief and the Reef

Posted on May 3, 2016 By shapeofthingstoni in Climate & greenhouse + Economics + Environmental economics + Politics & society + Science + Volunteering & activism

By now you’ve probably heard that there’s been a major coral bleaching event in Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. What you might not know is why it’s such a big deal, so let’s talk about coral bleaching: how it happens, why it happens, and what it means to the reef, to people, and to the planet.

Coral 101

Although there are two types of coral reefs – shallow tropical and deeper cool-water reefs – coral bleaching is only an issue for the tropic kind, so when I talk about reefs I’m talking about the coral communities found in calm, warm tropical waters in the shallow regions around islands or along edges of larger land masses.

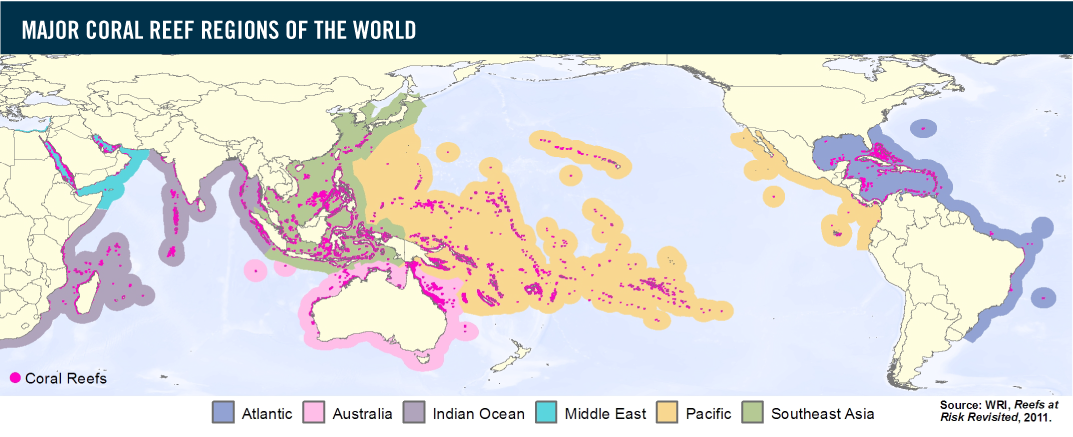

Coral reefs (dark pink dots) are found in calm, shallow tropical waters around the world. [1]

Coral reefs are formed over long periods of time in places where weather and ocean conditions are generally pretty stable. The hard mounds and ridges that form the structure of the reef are made of calcium carbonate: the remains of corals and other animals lived there [2]. Large reefs like Australia’s World Heritage-listed Great Barrier Reef take thousands of years to form, with living corals growing on top of their ancestors: a colourful living layer atop the reefs of time past.

Corals themselves are tiny little animals that are related to jellyfish (phylum cnidaria). What we think of as a single coral – the single structure – is actually a colony of teeny individuals all of the same species, living together as some kind of super-organism. They’re not on their own though: the corals take on boarders called zooxanthellae, wee single-celled algae that live within the coral animal’s body tissues. The corals and their algae have a mutually-beneficial relationship, with the corals keeping the algae safe from other critters who would eat them, and the algae supplementing the coral’s food source by sharing some of the sugars they may through photosynthesis [3]. It’s like having your own personal power plant just under your skin.

The wondrous bright colours of corals are a result of this happy cohabitation arrangement: pigments produced by the algae that get trapped beneath the coral’s skin. Without their algae boarders, corals lose their colour. Worse, without the sugars the algae provide through photosynthesis, the corals can’t catch enough food to meet their energy needs. Corals without algae turn white. This is called bleaching [4]. A bleached coral is a very stressed coral indeed, and there’s a pretty good chance it’ll die.

So what makes corals lose their algae pals? Read More

Share the conversation:

Know your environment

Posted on April 22, 2015 By shapeofthingstoni in Politics & society

Today is Earth Day.

I’ve spent it as I’ve spent most of the last eight weeks: inside, buried under required readings, assignment work, lectures and tutorials. While post-graduate study is challenging and intellectually rewarding, studying how to better care the environment feels like it is temporarily disconnecting me from much of it. My current life is very urban. I live and study in the inner city, surrounded by concrete, glass and steel. There’s precious little greenery and no wildness about Melbourne, but this, too, is the environment. This too is Earth.

When we think about environmentalism, about sustainability, about nature, we hold images in our mind like the photo above: a vast swathe of unspoilt Amazon rainforest. Places that take our breath away and make us want to protect them. Animals that inspire a sense of awe and wonder. This, we think, is worth protecting.

What about the every day places, the spaces we inhabit in our daily lives? This is our environment on the most intimate level: the space we interact with daily; the air we breathe, the ground we tread on, the food we eat. We are part of nature and these are the environments we create for ourselves. How then to value our cities and towns, these modified spaces? How to value properly the spiders, whose unappreciated efforts keep insect numbers down. How to value trees transplanted from elsewhere that never-the-less produce oxygen and filter pollution, anchoring themselves into paved-over soils and somehow staying alive? What about the once-wild streams now concreted and hidden beneath us? What about the pigeons and the sparrows that somehow manage to thrive here? This too is nature.

Today is Earth Day: a reminder to care for this planet and the forms of life that depend on her. A reminder that this planet is our environment, that we are part of nature: it shapes us as much as we shape it. The environment is not just the mystique of the Amazon or the brilliance of the Great Barrier Reef, it is the here and now of you and I, and how well we understand that, how we choose to value that, matters.

Today and every day in this still-unfamiliar city I am grateful: for the clean air I breathe, for the urban creeks I cycle by, for the exotic street trees in their autumnal glory, for the spiders and the sparrows, for the sky and wind and rain. This is my environment; something to care for, to protect and improve. After all, it’s keeping me alive.

Share the conversation:

Tags: cities, conservation, urbanism

Archives

Categories

Other places to find me

The shape of things to come